From businessman to watchman: Specialist shoemaker tells hardships after Empress Market operation

Specialist shoemaker, Tajdaar Khan, explains his journey from happiness to hardship after Empress Market operation

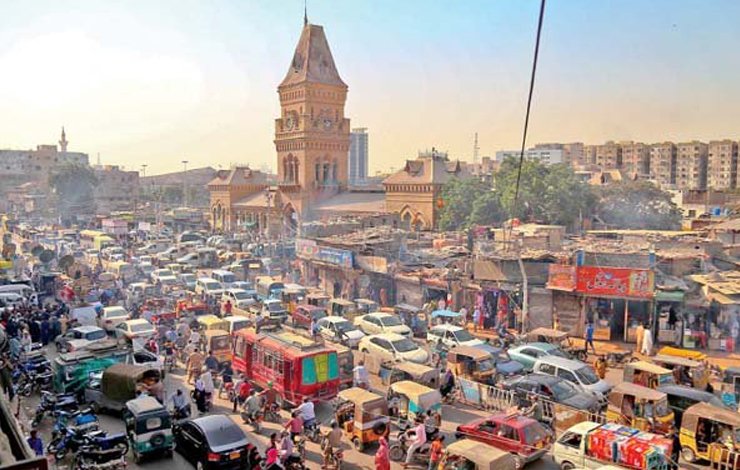

Tajdaar Khan’s journey from a traditional shoemaker of Peshawari chappals (sandals) is one of the untold stories depicted miseries of several shopkeepers who had been displaced after the Empress Market operation in November 2018.

A Pakistani journalist Alizeh Kohari unearthed the journey of Tajdaar Khan from a specialised shoemaker of Peshawar chappals (sandals) who kept in touch with him since Khan’s shop was demolished in front of him during Empress Market’s anti-encroachment operation on November 11, 2018.

Alizeh Kohari quoted Tajdaar Khan for the miseries he had faced after becoming a watchman at the same iconic market from a specialized shoemaker of Peshawari chappal, a traditional Pashtun sandal.

It’s been 3+ years since the shopkeepers of Karachi’s Empress Market had their livelihoods upended. Where are they now? Over the years, I kept in touch with one of them. For @GuernicaMag, one of the most heartbreaking stories I’ve ever reported. https://t.co/VNvOSMDi1i

— Alizeh Kohari (@AlizehKohari) January 12, 2022

Tajdaar had lived in Karachi all his life, but his family came from Kohat, a city in northwestern Pakistan.

Tajdaar Khan’s first memories of Empress Market are from when he was so little, he didn’t need to wear pants. He would accompany his father to their shop — Sardar Khan & Sons, in Garden No. 4 of the market — and watch him sew shoes.

At the time, they lived close enough, in a makeshift room above a nearby tea house, for Tajdaar to totter over, bare-bottomed, holding his father’s hand. When he was in eighth grade, his father developed hemorrhoids and his health began to fail.

Tajdaar — whose name means emperor, crown-wearer — dropped out of school and took over the business. He was good at it. He specialized in Peshawari chappal, a traditional Pashtun sandal: two bisecting straps of leather affixed to a sole made from truck tires.

Tajdaar, who thinks he is 57 years old but speaks tremulously, like a much older man, didn’t know any of this and even if he had, probably wouldn’t have been too bothered. His business was steady.

He sold his sandals for about 12 dollars apiece; they were worn by State Bank employees and staff at the Sind Club, a fuggy British-era institution where elite uncles puffed cigars and traded political gossip.

On the morning of November 11, 2018, Tajdaar Khan had received a telephone call by a hawker who asked him to immediate come there as everything at the Empress Market shops are being destroyed.

It was the time when bulldozers rolled into Empress Market in the early hours of November 11, 2018.

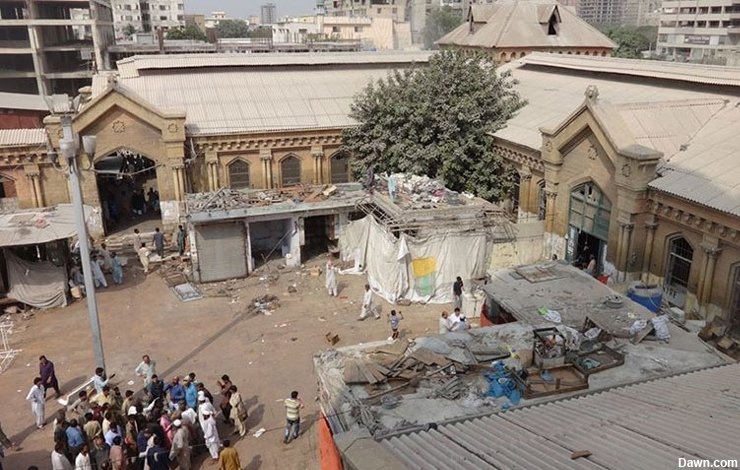

When the shopkeepers at Empress Market talk of the demolition, their stories have the jagged quality of footage from a camera carried by someone sprinting for cover. By most accounts, it started before sunrise.

Police filled the grounds. Sobs rang through the site. Some people brandished copies of official documents, reminding city officials that parts of the market were heritage sites. Their protestations fell on deaf ears. One distraught shopkeeper, a seller of kites, reportedly set his own shop on fire.

It took Tajdaar two hours to reach Empress Market after his neighbor from the next stall called him. This wasn’t unusual: he no longer lived close by, pushed over the years from the center of the city to its outer margins. When he arrived, it was nearly noon, and only his shop was standing.

Sobbing helplessly, he watched it buckle before a bulldozer. “Two rocks and a padlocked trunk,” he recalled. “That’s what remained.” Everything else had been looted, including 72 pairs of hand-sewn shoes.

By the time the machines stopped, at least 1,700 shops had become rubble. Three thousand hawkers had been uprooted. Researchers estimate 200,000 people lost their jobs. Later, the mayor revealed that that cash-strapped municipal government had to borrow machinery from a private developer, himself a notorious land-grabber, in order to carry out the demolitions.

Iftikhar Shallwani was appointed city commissioner in late October 2018, two weeks before bulldozers rolled into Empress Market in November 2018. A career civil servant, he’d spent seven years stationed in Buenos Aires and has since regained the chirpy zeal of the newly-returned. Shallwani is not a native Karachi-wallah; he grew up a few hours away in the city of Hyderabad, but visited with his father on weekends.

Over all, the commissioner considered the operation a success. “It was a difficult decision,” he admitted. “But, thank God, there were no casualties — no one was even injured. We did our due diligence. Now it looks clear. It looks beautiful.”

“This is our nishaani, memento”

Last year, in March, just before Karachi went into COVID lockdown, Tajdaar and I walked over to Empress Market, threading our way through the tooting glut of rickshaws, motorbikes and buses. At the entrance, he hesitated. “Whenever I come here, my heart aches.”

In the 14 months since, scraggly grass had grown on the grounds surrounding the market building. Also: an iron fence, six feet high, to prevent carts from trundling back in. Now, men sat in scattered clusters on the cleared grounds. Tajdaar walked over to a tree.

“This is our nishaani, memento. We planted it.”

Unprompted, he began conjuring his old world. “The dry fruit market was there. At the back, betel nut. This was our chappal market. The shops were all the same size. It wasn’t as if one was big, another small.” He paused for a minute, looking around, then continued. “Toffees and candies over there. Chemicals there. Towards the back over there was an alley. One alley, a second alley, a third one over there.”

People kept approaching Tajdaar, greeting him with the familiarity of old friends. An old man with carrier bags slung over one shoulder walked up and embraced Tajdaar. He carried groceries for customers — had done so for fifty years, he said, since he was a little boy — and would occasionally stop by Tajdaar’s shop for tea and talk. Tajdaar would repair his shoes; sometimes he’d make him a pair to send to family back in the village.

Sabir, one of Tajdaar’s old neighbours wandered over. “I’ve been roaming aimlessly, without work, for a year,” he said. In that time, there’d been two funerals in the family: his sister and father, both dead from shock and anxiety. Some of the shopkeepers have been allocated alternative shops elsewhere in the city — Sabir and Tajdaar, for instance, said they’d been allocated 16 square-foot commercial spaces deep within an abandoned building. Cats and dogs roamed freely there, and an open drain sat right next to the shops, they said.

Nearby residents claimed no shop had managed to survive in the complex for the past 30 years; it was surrounded by printing presses and stores selling wedding cards. Why would someone come and buy shoes there?

Tajdaar knew instinctively that he couldn’t revive his shop in the new location. “We would only lose money there, that much was clear,” he said. Sabir nodded. I asked why he was at Empress Market that day. “I come every day,” he said. “I don’t know. I guess we have a lot of memories here.”

“We go back a long way,” Tajdaar agreed.

Under the tree, right where Tajdaar’s shop stood, a light fixture had been affixed to the ground. It faced upwards, intended to illuminate the building’s freshly-scrubbed facade at night. “This is new,” Tajdaar said. “This is to tell the world, Look how we’ve made Empress Market shine.”

Night watchman

Tajdaar hadn’t strayed too far from Empress Market. He began working as a night watchman for a former neighbour, a dry-fruit storeowner: Hassan Abbasi, whose father used to sell nuts on a pushcart outside Empress Market, eventually upgrading to a permanent shop, then expanding to several others.

The Abbasis had become prosperous enough that, after the demolition, they could relocate with relative ease.

But customers had dwindled, Hassan said; if a hundred came before, 25 came now. “No one even knows there are shops in here,” he said, gesturing at the dim corridor, inside a commercial plaza a few blocks away from Empress Market. “What’s the point of a public market if the public can’t find it?”

A few feet away, Tajdaar crouched in front of a shuttered shop, sorting through a pile of cracked nuts. At night, as he kept watch, he shelled and sifted peanuts and pistachios; the Abbasis paid him an extra few hundred rupees for it.

He earned 14,000 rupees a month (then around $87), less than the minimum wage, at that time, of 17,000 rupees. His wife had begun washing other people’s clothes to supplement their household income; one of his daughters was still in school, while the other sewed clothes.

His younger son, a construction worker, contributed 500 rupees. His elder son struggled with addiction; on better days, he worked at a printing press. It didn’t pay much but kept him out of trouble, Tajdaar said with some degree of relief.

“Bus Allah paak ne yeh pardah rakha huwa hai,” he said. God has maintained this veil of respectability for us.

“Cannot afford bus fare to reach clinic”

After the demolition, Tajdaar had stopped taking his medicines. The pills were free, but he couldn’t afford the bus fare to and from the government clinic. “I pray to Allah,” he said, hunching his shoulders. “I say to Him, you do what is best for me.”

The doctor had advised against eating fatty meat; that at least, wasn’t a problem, because he could no longer afford it. Still, the children would crave beef, so he bought a quarter pound each week, to share between the six of them. After the virus outbreak, however, he began commuting home only once a week. Bus services had been pared down: it took even longer to travel and it cost more.

And so, he began spending his nights curled up on the floor outside the shuttered dry-fruit store. Months later, in the dead of the night in the middle of the pandemic, he would be mugged on the job, tied and bound and locked in a bathroom; later, his employers would pressure him into identifying the intruders to the police, which filled Tajdaar with such fear of retribution that he left the job altogether.

The bulldozers came to a halt in Empress Market a long time ago — they have clawed their way through other parts since — but the violence unleashed at that moment never stopped.

Now, Tajdaar’s best and only option is to spend his days and nights living and working a few blocks away from Empress Market — a man whose father named him emperor at birth, guarding in old age another’s kingdom.

This article is originally published in an award-winning non-profit magazine Guernica.